How youth activists are mobilising ahead of a landmark climate hearing

Vepaiamele Trief’s passion for climate justice began when she first learned about climate change in her primary school on the Pacific island of Vanuatu. Although lessons didn’t delve into the scientific details or the negative impacts it would have on society, she and her family have seen major changes even in the years since she was born in 2008.

“As a girl in Vanuatu, I see the effects of climate change, and I see how it affects our economy, our people and our children as well,” says Vepaia, as she prefers to be known. “We feel the heat and we see the unpredictable weather patterns. The cyclones are getting more intense. It’s affecting everyone.”

Vepaia is travelling to The Hague next week, supported by Save The Children, to take part in a landmark hearing on climate change at the International Court of Justice (ICJ).

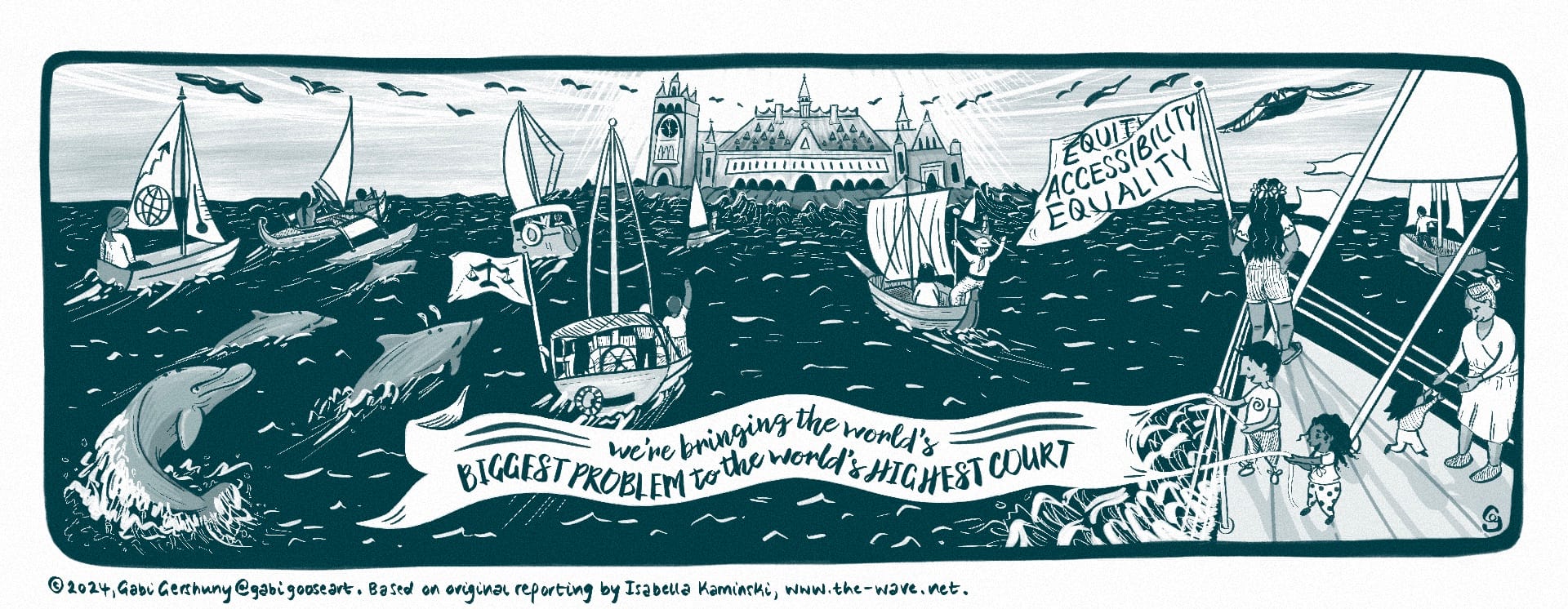

The two-week hearing at the Peace Palace, starting on 2 December, is the culmination of years of campaigning by a group of Pacific island law students, all of which took place as Vepaia went through secondary school.

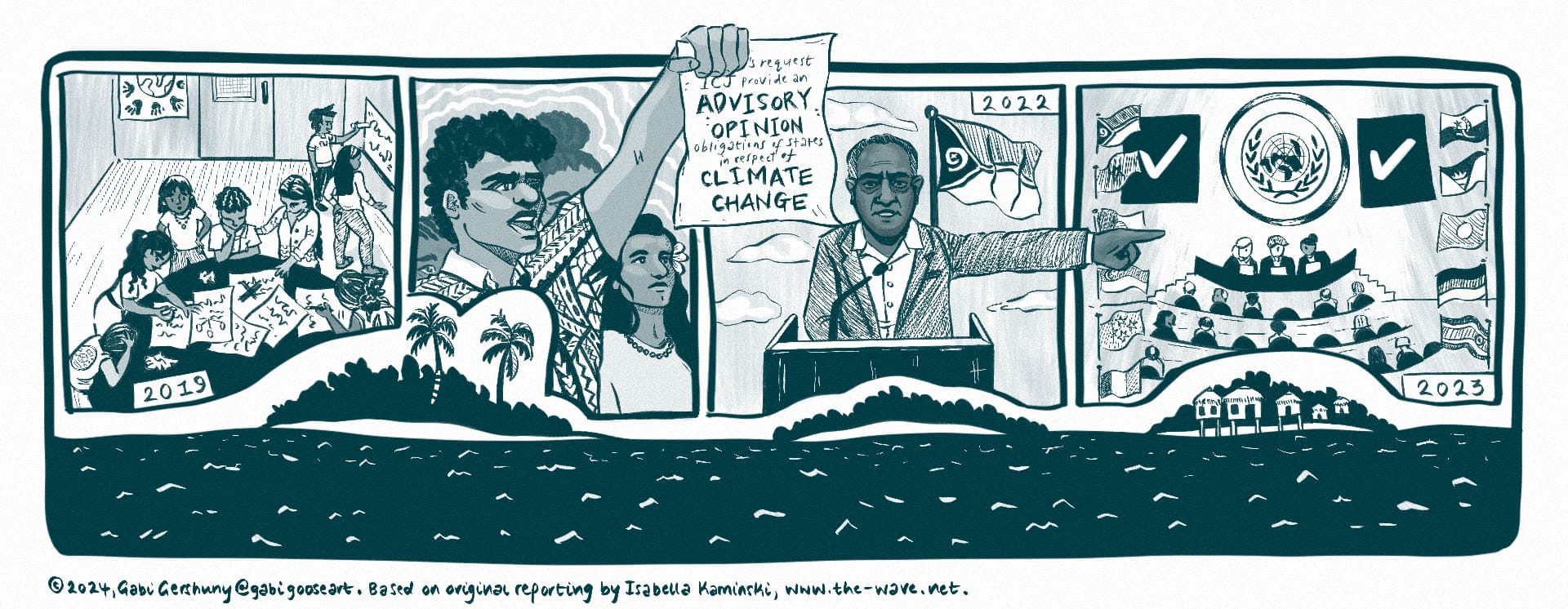

Organised into a formal organisation called Pacific Island Students Fighting Climate Change (PISFCC), youth activists helped move a theoretical legal discussion into a massive global operation that garnered support from thousands of civil society organisations and dozens of states across the world.

In March last year, the UN General Assembly approved a resolution calling on the ICJ to provide an advisory opinion on what obligations states have to tackle climate change and what the legal consequences are if they fail to do so on “peoples and individuals of the present and future generations”.

The decision was a landmark moment. Ishmael Kalsakau, then prime minister of the Pacific island of Vanuatu, which led the initiative alongside PISFCC and spearheaded diplomatic negotiations, described it as “a win for climate justice of epic proportions”.

Despite this success, the students did not rest on their laurels, recognising that the advisory opinion would only be as good as the quality of submissions the court received. Passing the baton between the hands of successive young people and working with peers at World’s Youth for Climate Justice (WYCJ), they developed a handbook to guide states and undertook intensive lobbying under the slogan 'We're bringing the world's biggest problem to the world's highest court’.

Siosiua Veikune, campaigner for PISFCC, says there is a huge disparity in states’ resources to produce these kinds of submissions, so there was a big emphasis on the involvement of civil society.

He says activists managed to get into the drafting rooms of some Pacific island states to discuss key topics affecting frontline communities such as sea level rise, internal migration and water scarcity. Alongside the science and the legal jargon, Veikune says it was important that submissions reflected these “lived reality stories”.

Activists say they succeeded in getting witness statements into the annexes of several states’ submissions including Tonga and Mexico. And they hope that, even if they were not used directly, they still had an influence.

Alongside states, a few organisations have been allowed to make formal submissions to the ICJ including the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), the World Health Organization (WHO), the EU and the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). This is in stark contrast to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, which is producing a similar advisory opinion but strongly encouraged a wide variety of organisations and individuals to contribute.

However, NGOs like Greenpeace produced their own legal briefs anyway, in which they included first-hand testimonies from individuals.

Furthermore, states are free to present their submissions to the court as they wish, so expect to see at least some including witnesses to climate change as well as the usual lawyers and diplomats. “We saw in the Inter American court hearings how powerful the direct testimony of indigenous leaders and others were,” says Nikki Reisch, director of the climate and energy programme at the Center for International Environmental Law. There is precedent for this in previous ICJ advisory opinions too.

Vepaia had hoped to be in the Peace Palace to speak as a climate activist as part of Vanuatu’s formal oral submission - a day which will coincide with her 16th birthday - but the government decided not to put her forward.

Nonetheless, Vepaia's presence and that of many other young people within the ICJ and in The Hague will put a particularly fierce spotlight on this court.

The Witness Stand for Climate Justice, set up by PISFCC, allows people to record their own stories ahead of the hearing. The idea, they say, “is about centering the human experience in a legal battle to make sure the stories of those at the frontlines of this crisis have a platform at the International Court of Justice”.

The organisation is also running a petition calling on the court to be ambitious, inspired by one during an earlier advisory opinion on nuclear arms that gathered a million signatures.

On the Sunday before the hearings start, there will be an opening ceremony with performances from the Pacific and the wider Global South - and likely some well-known speakers.

“Civil society has been present in this campaign since the very beginning,” says Veikune. “It was there in 2019 when it started. It was lobbying states in New York from 2020 to 2022 and it's been present throughout the submission phase as well. This gathering is essentially civil society carving out their own space outside of the International Court of Justice.”

"What happens outside the courtroom is every bit as important as what goes on inside"

During the two weeks, The Hague will see vigils, art exhibitions about the campaign and host a People’s Assembly where a panel of experts will listen to personal testimonies.

Activists hope that these events will draw public attention to the hearing, allow more people to participate and centre the stories of real people affected by climate change. “What happens outside the courtroom is every bit as important as what goes on inside,” says Richard Harvey, legal counsel for Greenpeace International.

Experts point to an earlier advisory opinion by the ICJ, which found that the UK’s separation of the Chagos Islands from Mauritius was a breach of international law and urged the UK to return the islands. Although this did not immediately happen, the UK did eventually relinquish control of the islands earlier this year.

“We like to think of courts and judges as in a bubble and removed from the influence of public narrative and life and policy and politics,” says Reisch. “But of course they're not.”

PISFCC has been crowdfunding to get campaigners to the Netherlands for the oral hearings and to the People’s Assembly in particular. In reality, says Veikune, activists are most likely to be coming from Europe since travel is so expensive. But the campaign is trying to rally diaspora and as many expats as possible. “We've always managed to rely on community and civil society, so hopefully they will show up for us.”

Mariana Campos Vega, Latin America deputy front convenor for WYCJ, has been busy reaching out to young people to tell them about the hearing and inspiring ‘watch parties’ around the world. She recently encouraged a group of Mexican law students to screen the hearing instead of a film during their regular movie night.

But she says it has been hard, particularly in the Global South, because familiarity with the ICJ is low, let alone the slightly nebulous concept of an advisory opinion.

During the hearing, PISFCC, WYCJ and environmental law experts will be providing real-time legal analysis of oral submissions “so that everyone is as well informed as possible so that it can’t be misconstrued by certain states”, says Veikune.

Youth activists will be holding their breath for an ambitious and progressive outcome from the court’s advisory opinion, when it finally comes out. But in the meantime they’ll continue to advocate for climate action in their communities and further afield.

Vega, who has been campaigning while finishing her law degree, is keen to emphasise that the work leading up to the hearings was a team effort. “I think if anything, this campaign has delivered on a blueprint for civil society and government collaboration,” says Veikune.