This lex is on fire

It was early morning when I first arrived at the Peace Palace as it sat quietly in the darkness and drizzle. Waiting for security to open, I was drawn to the perpetual flame that has burned continuously inside a stone pillar outside the building since 2002.

There is a beautiful history to this symbol of peace, which has whispered through every country in the world. But the blue flower at its base betrays the fact that the flame runs on gas, a suggestion to someone about to witness a landmark hearing on climate change of the depth of our current reliance on fossil fuels; try as I might, I could not imagine what else it could reasonably be powered by.

The law has increasingly been weaponised to further action on climate change in response to growing frustration at the lack of political progress. Nearly three decades of negotiations under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) have not succeeded in halting the rampant emission of greenhouse gases and a key issue – the exploitation of fossil fuels that have caused the vast majority of human emissions – is still only a small part of the discussion.

However, attempts to launch a lawsuit pitting states against each other faltered, so an ‘advisory opinion’ was conceived of to clarify existing duties in a less combative way.

AO, let's go

Three of the world’s top courts were asked to produce such a document.

The International Tribunal on the Law of the Sea was the first to do so, stating in May that greenhouse gases are pollutants that are wrecking the marine environment. The Inter-American Court of Human Rights held its own hearings in Barbados and Brazil earlier this year.

That left the International Court of Justice (ICJ), an institution whose role is to harmonise and integrate international law.

Following years of campaigning by a group of Pacific island students and diplomacy spearheaded by the nation of Vanuatu, the UN General Assembly last year unanimously called on the ICJ for just such an advisory opinion. Its request was framed around two key questions: what obligations do states have to tackle climate change under international law and what are the legal consequences if they fail to do so?

After two rounds of lengthy written submissions, the court invited states to present their cases orally in The Hague.

Over two weeks, I watched just shy of 100 states appear before a panel of 15 judges. Their chosen diplomats, lawyers and occasionally activists gave statements that were in turns passionate and apathetic, articulate and mumbled. Some wore the mask of cool professionalism, while others simmered with righteous anger. A few were there mainly for money. A few looked close to tears.

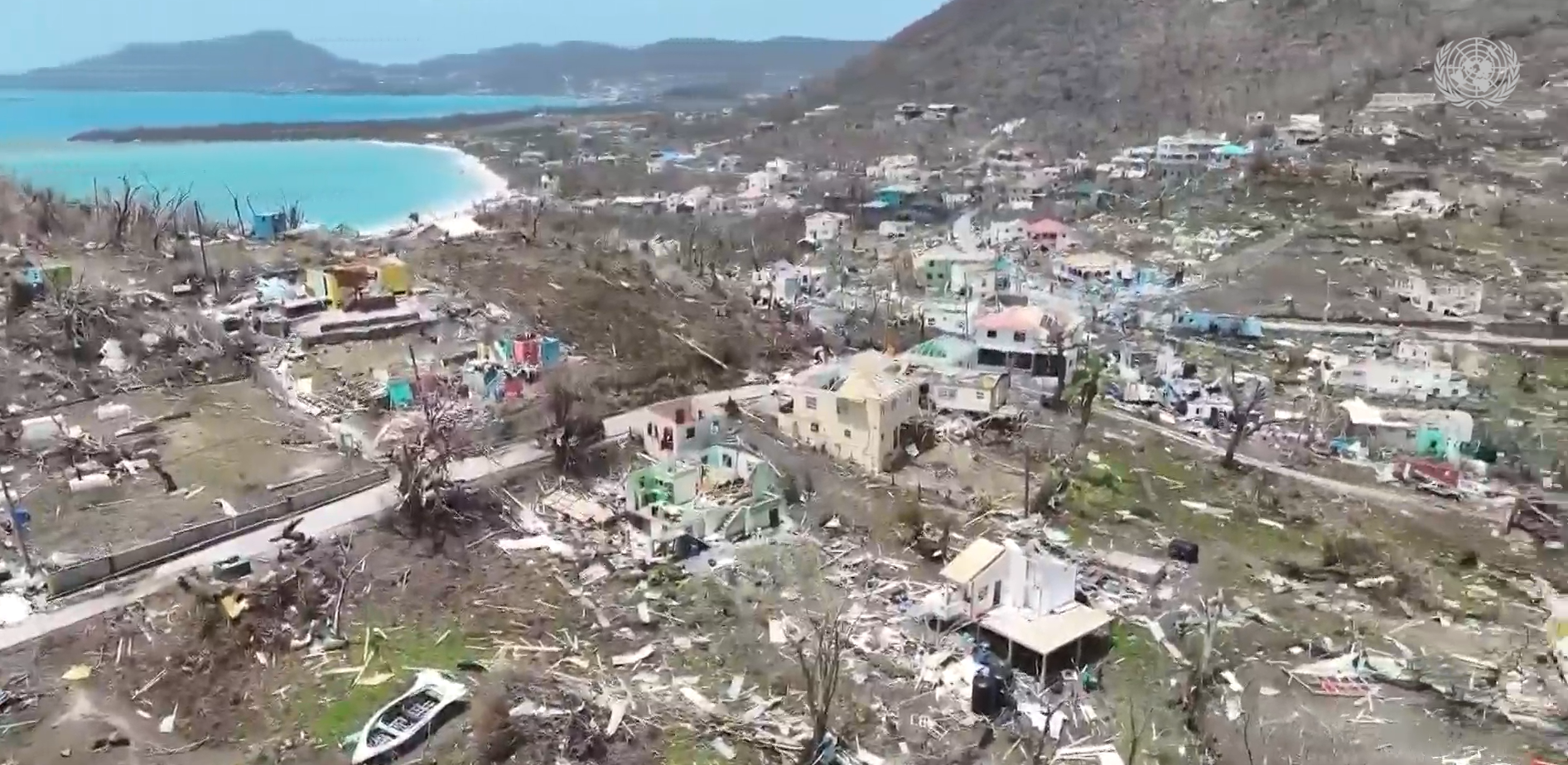

So much for non-combative; the opening shots were fired by Vanuatu and the Melanesian Spearhead Group, which underscored the existential threat their islands faced. Cynthia Houniuhi, president of Pacific Island Students Fighting Climate Change, said her people’s land of Fanalei, on the Solomon Islands, was on the verge of being completely engulfed by the rising seas. “Without our land, our bodies and memories are severed from the fundamental relationships that define who we are," she said.

Those standing beside her pointed the blame squarely on “a handful of readily identifiable states” that had produced the vast majority of greenhouse gas emissions but stood to lose the least from their impacts.

That handful hit back, with Australia, the US, the UK, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, China and Russia attempting to limit legal responsibility exclusively to the UNFCCC and its 2015 Paris Agreement and denying that human rights had any bearing on the questions at stake. That argument was tempered by some wealthy nations, such as Germany, but the message was largely the same.

While there was recognition that the impacts of climate change are distributed unfairly and not all had contributed equally to the problem, most strongly denied any historic accountability.

These submissions did not go down well with activists who pointed out that there is no mechanism to enforce compliance with the core of the climate treaties: their national emission targets. Even Laurence Tubiana, an architect of the Paris Agreement, said it should not be misused by countries to “dilute their climate responsibilities”.

Frontlines

I do not buy the suggestion that these statements were surprising. That obscures how deep the resistance to accountability goes, written deep into the bedrock of political institutions and largely unswayed by who is currently in charge. And it’s important to note that Paris Agreement was deliberately worded to state that it “does not involve or provide a basis for any liability or compensation”.

The UK - my country - is a good example. Most states did not accept the UK’s explicit attempts to distance itself from other big polluters. But attorney general Richard Hermer, representing a new Labour government keen to revive its climate leadership image, seemed almost surprised when I challenged him on this point.

What was more profound was the way in which countries on the frontlines of the climate crisis, particularly Pacific and Caribbean island nations, carved out their own space at the court, bringing in colour, vision and a firm sense of place and identity.

With equal time on the podium, the majority roundly rejected the argument that climate treaties were lex specialis - a principle where a specific law overrides more general ones, and I promise the last legal term I’ll use. Zachary Phillips, counsel for Antigua & Barbuda, pointed out that the logical implication of this claim “would leave the world less well protected than if these treaties had never been concluded”.

Instead, they argued that a wide range of international law applies, including treaties and customary rules on due diligence, the duty to cooperate and the prevention of transboundary harm, as well as the right to self-determination. Human rights are being harmed, they said, including those of children and future generations.

There was some support from the heavyweights. The EU, representing its 27 member states, also rejected the idea that the Paris Agreement was the only relevant law and said states do not have unlimited discretion to decide their own contributions - an intervention that could have been missed in the graveyard slot on the last afternoon.

'Unforgiving tide'

While the speeches were solidly grounded in the nitty gritty of the law, this was also a space for making broader political statements.

Participants unburdened themselves of long-held hurt, pointing to the historic injustices that underpin the unfolding crisis.

Hot on the heels of the country that wrought the industrial revolution, representatives of St Lucia delved straight into the island’s past as a colony of both the UK and France. Legal counsel Jan Yves Remy warned of an “unforgiving tide threatening a dark future” that her people had no hand in writing.

It was one of many delegations, from the Cook Islands to Micronesia, Nepal to Tonga, that repeatedly called out the role and continuing impacts of colonialism and racism in climate change. These states demanded financial compensation, as well as a variety of more structural reparations including debt cancellation and assurances of continued statehood if land is permanently lost.

During these presentations, nations described and showed the impacts that climate change is already having on their people; forced relocations, deaths in the choking heat, the loss of staple foods of huge cultural significance such as yam and coconut, graveyards being washed away and livelihoods under threat.

**

In their eagerness for an advisory opinion that supports their petition, advocates don't always acknowledge the potential downsides.

The opinion may simply be rejected by countries with the most political influence. And such a rejection could further erode the rule of law that Switzerland has already attacked by metaphorically sticking the middle finger up at the European Court of Human Rights following that court’s first climate judgment.

The outcome could be conservative in a way that sets back legal and political efforts. After all, the UN agreed to ask for this unanimously and many states would not have done so had they anticipated a massive change in the status quo that currently benefits them.

It could even, as wealthy nations warned, undermine the “carefully negotiated” climate treaties; what Margaret Taylor, legal adviser to the US Department of State, described as the “clearest, most specific and most current expression of states’ consent to be bound by international law in respect of climate change”.

And the whole thing may simply be too slow to respond to the urgency of the climate crisis.

Truth to power

But it has to be seen in a broader historical context, in which judicial statements have deeper and long-running impacts than can immediately be foreseen.

What is clear is that victims have had the chance to tell their stories and speak truth to power on a global stage.

States have been forced to express their views in public and can now be held accountable to them by their citizens. There is no doubt that this hearing has burned away layers of obfuscation around multilateral talks, bringing to light what the governments of major polluters really think and making a clear distinction between geographical and political vulnerability. That shifts the international dynamic, colouring conversations behind the scenes as well as those in front.

Lawyers and campaigners will also be ready to carve the advisory opinion into climate lawsuits around the world, even though it is not in itself legally binding.

And finally, it is notable how many states had national or regional representation, in defiance of the ‘ICJ Mafia’ that so often dominates this institution. Whatever happens, the process has succeeded in building legal capacity and expertise in the Pacific, in Africa, in the Caribbean.

A giant effort

I’m wary of David and Goliath stories, so it’s important to stress that all this was the result of concerted and strategic action.

A network of experts supported states with no previous experience at this court or which lacked the resources to forge legally and scientifically sound submissions.

States were encouraged to reimagine what the law could do. Julian Aguon, a lawyer who represents the Melanesian Spearhead Group through Blue Ocean Law, has sought to centre Indigenous conceptions of the world, what he describes as a different legal “imagination”. And he told me that Pacific island teams brought “the fullness of their lived experiences” to the process.

Ongoing coordination, although sometimes butting up against state self-interest and individual ego, helped present a largely unified front that outweighed the biggest emitters, even with the mass of the latter group’s economies and political histories.

There were also remarkable efforts to elevate the voices of marginalised peoples within these states, weaving a powerful narrative of ongoing as well as future impacts. Aguon conceives of this work as a “spiritual duty”.

At the heart of all this were the young people that sparked the whole idea in a law class at the University of the South Pacific over five years ago. Together with peers in Europe, Asia, Africa and the Americas, they campaigned relentlessly until world leaders were ready to approach the court. And then they mobilised again to encourage governments to submit strong statements, to raise public awareness of what could have been an obscure legal process and to encourage people to attend in person or though virtual ‘watch parties’.

In The Hague, youth organisers held a joyous and moving opening ceremony that set the stage for the hearing through song and dance, as well as a People’s Assembly and cultural events throughout the city.

Burning the candle at both ends, this group of nations and individuals made a powerful appeal for climate justice to the ICJ; that the states that have done the most damage do not just have a moral responsibility to those that have done the least, but a legal one.

I do not know whether the court is ready to make such a leap of imagination and the inscrutable faces of the judges gave little away. Although it is a different institution, I can’t help contrasting it to the engaged judicial panel at the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, whose president explicitly said she wants its advisory opinion to have a “profound” impact.

But law does not exist in a vacuum. Campaigners are keeping up their pressure on the ICJ, which will make key decisions about the direction of its opinion in the next month or two, and will try to ensure a progressive conclusion - if it comes - has fertile ground on which to land.

“On occasion, international law may be magnificent,” Aguon gushes with a smile, despite his clear exhaustion, and I cannot help but smile back. Having watched the hearing closely, I think states fighting for their physical, economic and cultural existence have done all they can to present the ICJ with an intellectual and emotional challenge. And it helped me reimagine what justice in the context of climate change means.

I spend my last evening in The Hague in a tiny cinema at the screening of a film that traces the impossible journey of the student team alongside many of the young people themselves. (It’s called YUMI - The Whole World and I highly recommend it). They watch each other traipse through the corridors of power and laugh as they struggle with the awkward mechanics of campaigning.

As a journalist I'm an outsider to this scene, so I leave them there, sharing the warmth of their friendship and the certainty that they are doing the right thing. A fire has been being lit, fuelled by something altogether more sustaining.