Why the International Criminal Court should investigate environmental crimes

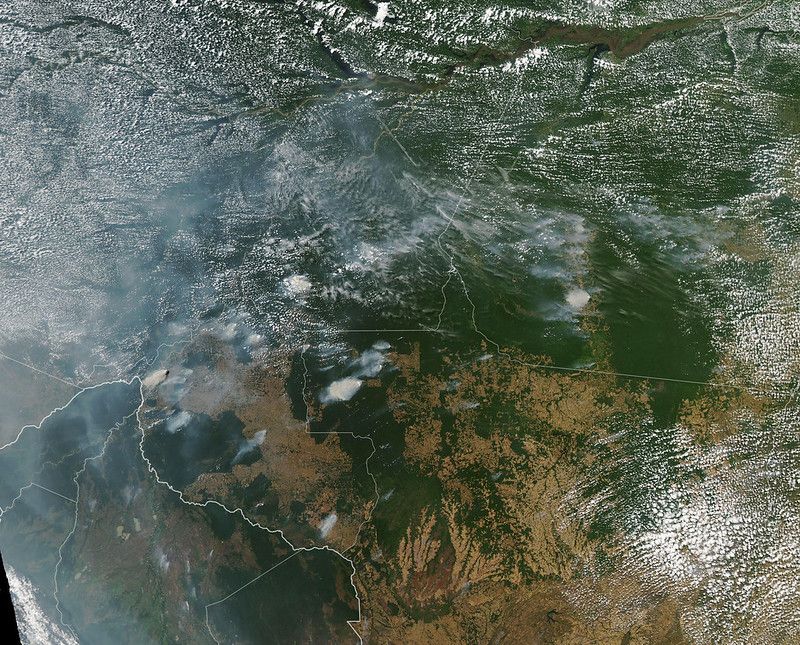

On 10 August 2019, vast sections of rainforest in central Brazil were set alight as part of a coordinated action by ranchers, loggers and land-grabbers to clear illegally deforested land. The ‘Day of Fire’ sparked record blazes in the region, but it was just another example of deliberate destruction of the Amazon for which people are rarely held accountable.

A healthy and thriving Amazon rainforest is essential for the Indigenous people that live there, holding within its boughs hundreds of unique cultures, languages and traditional knowledge, as well as a huge amount of animal and plant species that may never be recovered, let alone recorded. And it is indispensable for the world as a whole because of its role as the largest carbon sink.

But it has been under sustained attack over the past few decades, with deforestation rates repeatedly breaking new highs.

That’s why campaigners around the world are urging the International Criminal Court (ICC) to open up a formal investigation into what has and is continuing to happen there.

Dossiers of destruction

The ICC is cagey about the information it receives, citing confidentiality issues. But over the past three years, it has been sent at least five formal complaints - known in the court’s lexicon as ‘communications’ - alleging serious crimes taking place in the Brazilian Amazon.

The first, in November 2019, was submitted by two human rights groups (Human Rights Advocacy Collective [CADHu] and the ARNS Commission) who demanded an investigation into then president Jair Bolsonaro for incitement to commit crimes against humanity and to commit genocide of Brazil’s Indigenous peoples and traditional communities.

Paris-based lawyer William Bourdon, representing Indigenous chiefs Almir Suruí and Raoni Metuktire, made similar accusations against Bolsonaro in January 2021.

Later that summer the Articulation of Indigenous Peoples from Brazil (APIB), which represents almost a million Indigenous people, demanded an investigation into both crimes against humanity and genocide. This was the first time in history that Indigenous peoples had put themselves before the ICC - with the support of Indigenous lawyers - to defend themselves against these crimes.

In October 2021, international NGO AllRise filed another complementary complaint, which again accused Bolsonaro of crimes against humanity. It claimed he directly and indirectly facilitated and accelerated the devastation of the Brazilian Amazon, leading to intentional and uncontrolled environmental devastation.

A few months later it sent a supplementary note, warning that deforestation was accelerating. “This indicates that Mr Bolsonaro and his administration have made no effort to slow down or halt deforestation. As outlined.. climate science demonstrates the clear link between rapid acceleration in deforestation and fatalities, devastation and insecurity on a regional and global level.”

AllRise called for an “urgent and immediate criminal investigation” by the ICC.

"Climate science demonstrates the clear link between rapid acceleration in deforestation and fatalities, devastation and insecurity on a regional and global level"

While all these communications relate to slightly different crimes, they have in common deep concerns about the ongoing destruction of the Amazon rainforest in Brazil and both their local and global effects.

The ICC’s prosecution office (OTP) has launched famous many criminal cases over its 25-year history, including those against Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi and the perpetrators of war crimes and crimes against humanity in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

But, although it began a ‘preliminary evaluation of jurisdiction’ into the first complaint about the Amazon in late 2020, it has yet to respond to the others.

When asked if it had ever opened an examination or begun a prosecution with a significant environmental component, the ICC could only point to its 2008 charge of then Sudanese president Omar Al-Bashir with genocide. The case highlighted the connection between genocide and the deliberate destruction of the environment by systematically destroying properties, vegetation, and water sources and repeatedly destroying, polluting or poisoning communal wells or other communal water sources by the militia and Janjaweed in Darfur.

Anthropocentric crimes

When it receives complaints , the ICC has the choice of conducting a preliminary examination before opening a full formal investigation. Among other things, it will look at whether any genuine investigations or prosecutions are underway in the country in question and whether the alleged crimes are serious enough for the ICC to intervene. When considering that last point, one of the factors it takes into account is the social, economic and environmental damage inflicted on affected communities.

In 2016, chief prosecutor at the time Fatou Bensouda said her office would "give particular consideration" to crimes committed by or resulting in "the destruction of the environment, the illegal exploitation of natural resources or the illegal dispossession of land". However, her leaving statement five years later made no mention of the environment.

Kate Mackintosh, executive director of the Promise Institute for Human Rights at the UCLA School of Law, says it is very difficult for the ICC’s current remit, which is underpinned by the Rome Statute, to fully account for environmental crimes because it is “very anthropocentric”. The only current reference to the environment is in relation to war crimes and criminalises “intentionally launching an attack in the knowledge that such attack will cause... widespread, long-term and severe damage to the natural environment”.

“I think it's really important for the court to use existing crimes where appropriate to prosecute environmental destruction and to take that into account," says Mackintosh. "But while destruction of the environment will have devastating effects on a human population, it can’t always be framed as an attack on a human population.”

Making the argument that climate change is a criminal offence could be even harder; nearly all climate litigation to date has been under civil law. “It's definitely more complicated to deal with,” says Mackintosh, who is deputy co-chair of a legal panel drafting an addition to the Rome Statute to include the crime of ecocide. “It's becoming easier because of all the developments in attribution science but it's a work in progress.”

That has not stopped a coalition of young people in the UK and New Zealand asking the ICC to open an investigation into oil major BP.

Their communication, submitted today, claims the company's senior executives tried to maximise their oil profits despite the human suffering inflicted and an understanding of the risks. It argues that the widespread and harmful nature of climate change means classifying it as a crime against humanity is the only accurate legal definition (BP did not respond to a request for comment).

Students for Climate Solutions New Zealand and the UK Youth Climate Coalition have given the court a year to decide whether to start an investigation; based on its responses to previous communications, that seems ambitious.

Not just a war crimes tribunal

With the International Court of Justice soon to be asked to give its advice on human rights and climate change, and the US planning to slap sanctions on those behind deforestation in the Amazon in a bid to tackle the climate crisis, the ICC is now looking distinctly out of step.

Growing increasingly frustrated, the groups behind the Brazilian communications wrote a joint open letter to the ICC’s current chief prosecutor Karim Khan in May 2022.

They welcomed the court’s “swift opening” of an investigation into crimes committed by Russia in Ukraine and said they were aware that this work would require a lot of money and manpower. “However we also think, and this is the concern of many NGOs, that notwithstanding how crucial this investigation is, it should not hinder the OTP from opening and conducting other investigations which are just as urgent and essential for the international community,” they wrote.

It’s ultimately up to the ICC whether it decides to investigate. But campaigners say it must start prioritising environment-related cases.

“International lawyers are still fixated on armed conflict [but] the ICC is not just a war crimes tribunal,” says Richard J Rogers, international criminal lawyer and executive director of Climate Counsel.“It can investigate crimes in both wartime and peacetime and I’ve argued several times that prosecutors can have more impact if they investigate cases committed in peacetime because the perpetrators have more to lose.”

Climate Counsel was one of three organisations, alongside Greenpeace Brasil and Observatório do Climato, to recently submit another communication to the court, claiming to provide evidence that an organised network of politicians, civil servants, law enforcement officers, businessmen and other criminals carried out a systematic attack against rural land users and defenders in the Amazon region.

Their dossier includes details of more than 12,000 land or water-related conflicts in the Brazilian Amazon over the past ten years, with crimes including murder, persecution and inhuman acts against Indigenous Peoples, traditional communities and other vulnerable groups.

It also outlines the international climate impacts of all this destruction. “If the Amazon is to help save the world from lethal global heating,” says Paulo Busse, lawyer for Greenpeace Brasil and Observatório do Clima, “the mass crimes against those who protect the rainforest - rural land users and their defenders - must stop."

The communication is accompanied by an online platform that hosts testimonies of survivors, photographic evidence, 3D reconstructions of crime scenes, visualizations of data, analysis of satellite images and deforestation data.

Rogers says it provides ICC prosecutors with “a really solid foundation to put a case before the judges of crimes against humanity” in the absence of an international crime of ecocide.

It also provides prosecutors with the beginnings of evidence of individual criminal responsibility, he says. A confidential annex highlights a number of people the NGOs believe should be persons of interest. “There are some pretty obvious candidates for prosecution,” says Rogers. “And many less obvious ones.”

With Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva due to take over the Brazilian presidency in January, hopes have been raised that the nation’s environmental record will improve. He has promised to tackle “all crimes” in the world’s largest rainforest, from illegal logging to mining, affirming that "there will be no climate security if the Amazon isn't protected”. A recent report by development think tank Igarapé Institute, the Brazilian Forum for Public Security and the Sovereignty and Climate Center offers a road map for how this could be achieved.

But Rogers says the groups involved in the latest complaint took a different approach from previous communications because “the reality is a bit more nuanced”. “The crimes have been going on for a long time - before Bolsonaro came to power - and it’s much more about an entrenched system that needs to be dismantled. Bolsonaro is very obviously part of that and perhaps its most vocal champion. But he is not the system itself.”

Tipping points

Whether anyone will be held accountable for all the damage to the Amazon remains to be seen. Johannes Weseman, founder of AllRise, believes the ICC wanted to wait until the Brazilian elections were over to react to communications about Bolsonaro and hopes his organisation will receive a response by the end of the year. “But of course we cannot be certain.”

With evidence of its declining resilience and reports that some parts of the Amazon have already reached a ‘tipping point’ - where they have degraded into savanna and can no longer revert to rainforest - these calls have never been more urgent.

"If the ICC wants to play some kind of positive role in addressing the climate crisis, then it needs to start investigating these kinds of cases”

The court itself remains inscrutable. One of its prosecutors told The Wave they saw “no value in anyone from outside speculating” about the prosecutorial office’s strategic choices and priorities.

Macintosh says the court is “really split between trying to be a very conservative legal institution and a global player”, and suggests taking on more environmental cases would help it retain its credibility and be more relevant to younger people.

Weseman is somewhat sympathetic. He tells The Wave that he understands that most ICC resources are now occupied by the investigation against Russia and describes the ICC as systemically “underfinanced and understaffed”.

“Nevertheless,” he goes on, “we think it is time for the ICC to act now. The public (we have collected over a million signatures with two petitions) deserves a response.”

Rogers, who is still waiting for a response to a communication he submitted to the ICC eight years ago about land grabbing in Cambodia, urged the court to take up the environmental baton. “The ICC can have a real impact not only in relation to the particular country or situation but in relation to many similar situations around the world.

“Obviously we’re dealing with massive environmental crimes and human rights abuses that will cause or contribute to global warming. If the ICC wants to play some kind of positive role in addressing the climate crisis, then it needs to start investigating these kinds of cases.”