‘Disturbing’ rise in just transition lawsuits threatens to derail energy transition

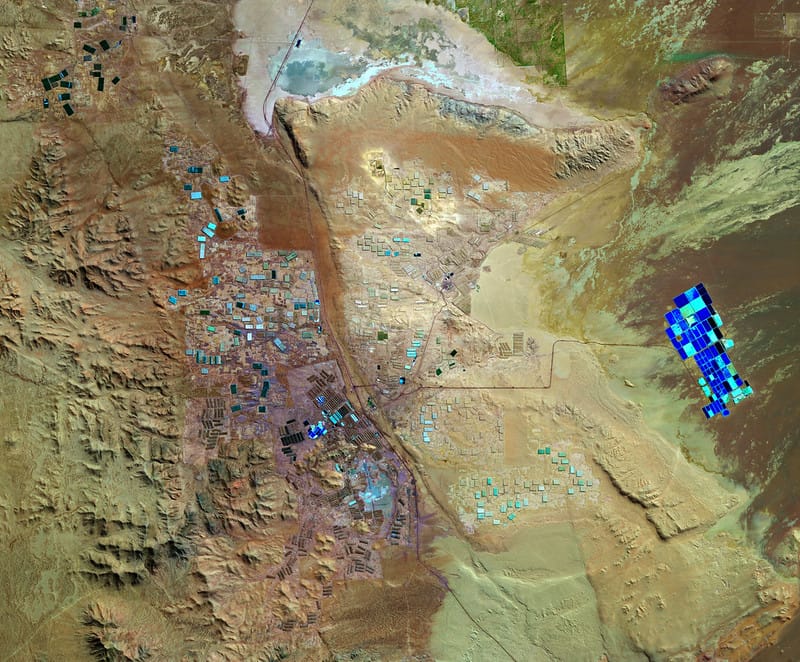

Mining bauxite is a lucrative industry in Jamaica, as is refining it into aluminium. Demand for the light, flexible metal has grown to satisfy an insatiable global demand for everything from aircraft and building materials to technologies essential for a transition to clean energy such as solar panels, wind turbines and batteries. In response, Jamaica has issued more and more permits to dig out and process its valuable ore.

On such a small island, however, industrial activities are never far from peoples’ homes or the farmland and ecosystems they rely on. In 2022, nine people sued the Jamaican government for granting environmental permits to Noranda Jamaica Bauxite Partners II to mine bauxite and other minerals on over 1,300 hectares of land in St Ann, on the country’s north coast.

The group says mining is breaching their constitutional rights by damaging their homes, farms, water and health - concerns shared by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. A major problem with the refining process is that it uses huge amounts of caustic soda, which pollutes watercourses and can cause serious health problems. One claimant, Victoria Grant, blames the industry for the death of her husband.

Last year, the Supreme Court ordered a halt to the project, pending the result of the case.

The dark side of the moon

Reading most media coverage of climate litigation, it would be easy to conclude that it’s single-mindedly in pursuit of an atmosphere less stuffed with heat-trapping greenhouse gases. I’m sure I’ve been guilty of this myself.

But the constantly growing figure on the face of the LSE’s annual report, mainly based on the Sabin Centre’s database, doesn’t just tally up these kinds of cases.

Some lawsuits are filed by corporations challenging public policy, such as the lawsuits that have forced a halt to the Securities and Exchange Commission’s climate disclosure rule in the US. In other cases, companies are using the law to quell climate activism in the streets or in the boardroom.

The Jamaican bauxite lawsuit is part of another steadily growing subset of cases, known as just transition litigation, which challenge governments and companies to address the climate crisis without trampling over people or the environment.

Annalisa Savaresi, professor of international environmental law at the University of Eastern Finland, says research into human rights litigation has tended to focus on cases that explicitly support climate action, what she calls “the visible side of the moon”. But for a few years now she has been concerned with exploring the other side “that was possibly bigger, much more complex and yet unexplored and significant”.

Savaresi does not think lumping these lawsuits in with climate litigation has been helpful. “The relationship between these two phenomena is very important to unpick, because what we're really interested in is to understand the role of courts and litigation in achieving net zero societies and to address conflicts.”

In a forthcoming paper, Savaresi (and many co-authors) set out to define just transition litigation so that it can be better quantified and understood.

They include work-related claims - for example job losses following the closure of fossil fuel infrastructure or climate policies that raise business costs - and legitimate attempts to uphold property rights, of which there is a long tradition in planning law against energy projects in Europe and the US.

Claims under growing corporate due diligence obligations are another important area. In one case, indigenous farmers from southern Mexico were recently given permission to bring a claim against energy firm EDF in France. They say the company failed to prevent violence and intimidation of residents who opposed a massive wind farm on their ancestral land, breaching French law. The EU’s new directive could also provide the basis for future human rights litigation.

Challenges to climate adaptation projects, especially those that require vast amounts of land, would be included too if they materialise.

Others have begun exploring this topic too. A report published a few weeks ago by the Business & Human Rights Resource Centre (BHRRC), Unjust transition on trial, found a “disturbing” rise in lawsuits against renewable energy and transition mineral mining projects for systemic human rights abuses. You can explore their database below:

The BHRRC says these are “largely” community-driven challenges; three quarters were brought by Indigenous and/or other frontline communities seeking to protect their rights, albeit some with the support of NGOs, following a similar pattern to wider climate litigation in the Global South. They do this even though resistance is expensive and dangerous.

In some cases, public authorities within a country disagree about how projects should be handled. For example, the regional government of Atacama in Chile sued the national government after the latter called for an increase in lithium production in the region without public consultation. Lithium is a key component of many technologies needed for a low-carbon transition.

Most of the lawsuits analysed by the BHRRC are in the Americas, and they identify various problems with projects they challenge.

The local environment is nearly always raised; three quarters of the 60 cases analysed refer to the right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment, and 80% relate to water pollution and/or access.

Nearly half (45%) of cases challenge the impact of projects on peoples’ livelihoods, mainly violations of land rights or the impact of projects on notable or protected areas.

A third challenge the way projects have been approved, arguing communities were not properly consulted.

It’s the system, stupid

Most of the cases identified by the BHRRC are about the extraction of minerals used for technologies key to a clean energy transition, such as batteries for electric vehicles.

The mining sector has long been problematic for land grabbing, polluting water sources or extracting too much, soil contamination and more. So it’s not a surprise that it continues to be the subject of fierce resistance in many countries, for example around copper and lithium.

But cases against renewable energy projects are also rising and the problems are nearly identical. Hydropower is the focus of 15% of lawsuits identified by the BHRRC, most of which are concerned about access to water. The remainder challenge solar and wind; unsurprising given they make up the vast majority of renewable projects.

“Past human rights abuses associated with oil and gas extraction or other extractives are now being replicated in the field of renewable energy generation,” says Savaresi.

As more and more renewable energy gets installed, the BHRRC expects litigation to increase in this sector, highlighting “the commonalities in vulnerability of frontline communities and workers regardless of the point at which the transition to clean energy intersects with their daily lives”.

Some of these cases succeed. In Taiwan, Shengli Energy’s permit for a solar farm project was revoked in 2022 after an Indigenous Katatipul community argued they had not been properly consulted. (According to BHRRC, the case is still ongoing).

And in Brazil, Vale’s Onca Puma mine was recently forced to stop operating following legal disputes with local communities and the state.

Another example happened last year, when Panama’s Supreme Court ruled that First Quantum Minerals’ contract to operate its giant Cobre Panama copper mine was unconstitutional after widespread public protests against the project.

But as is so often the case the only potential winner here is a corporation: the protests got so heated that people were killed; First Quantum has since begun international arbitration against the Panamanian government over the loss of the mining contract so the country stands to lose millions; and if the mine remains closed there will be significantly less copper on the international market for clean energy tech. The abrupt closure has also led to ongoing pollution concerns.

A case that could elevate just transition lawsuits from a local to an international concern is a referral to the European Court of Human Rights over heavy metal pollution from mining in southern Spain.

It’s worth pointing out that these analyses are not exhaustive, partly because finding out about these lawsuits is tricky. They are often brought by communities without the financial or media resources of a big NGO and lacking the kind of international coordination that climate-focused litigation has benefited from. They are also under-reported, lacking the sexiness of the climate litigation narrative and perhaps inspiring fears of fuelling climate denial.

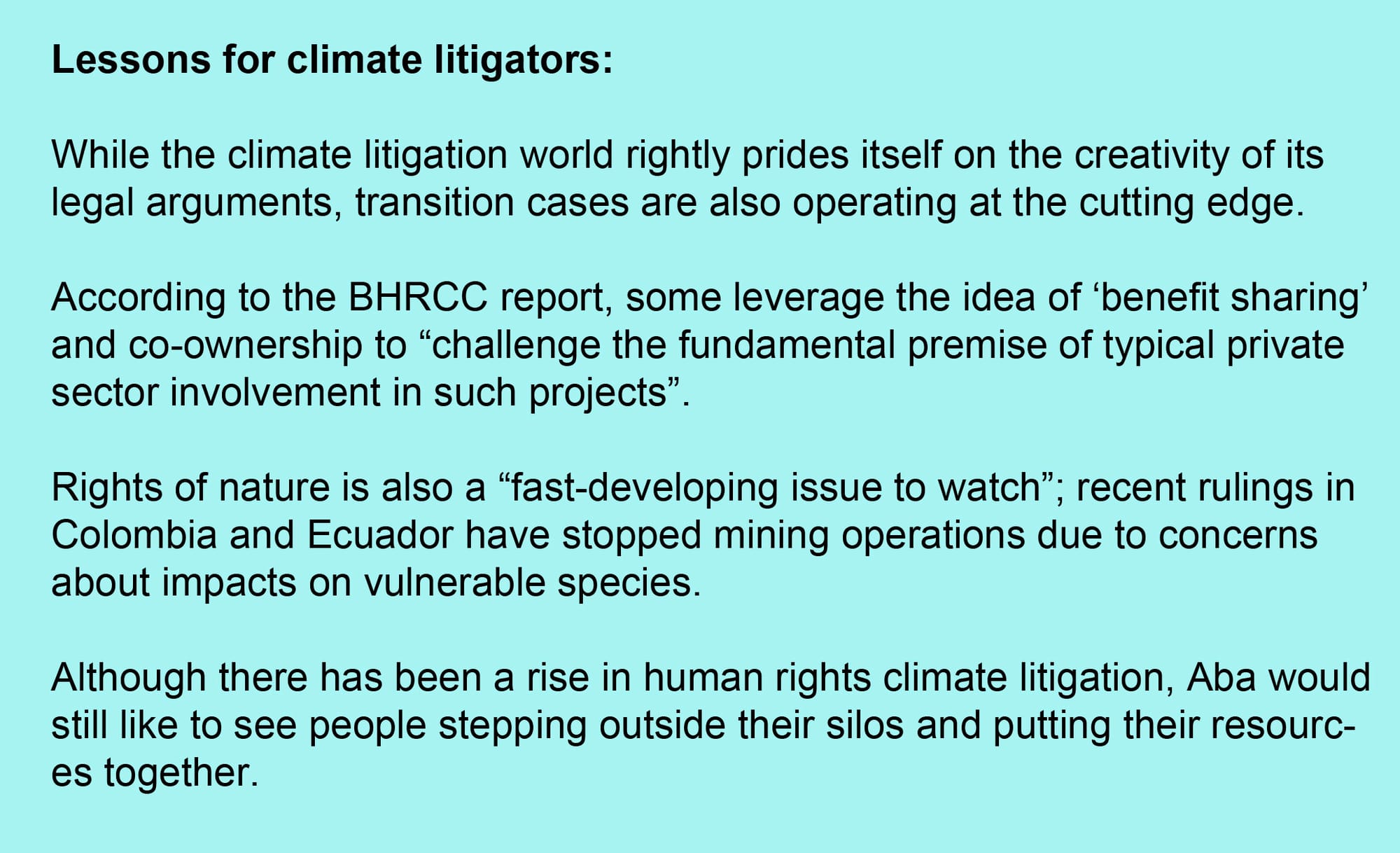

But, unlike rising investor-state dispute settlement claims against governments in relation to minerals needed for clean energy or opposition to offshore wind projects linked to climate denial groups, legal experts say just transition lawsuits raise important questions about the fairness of the clean energy transition and whether global development must always be predicated on extractivism.

And they are a barrier to addressing climate change. The BHRRC says such litigation threatens to “derail” the energy transition if the concerns underlying it are not addressed, a result “the world can ill afford”. Projects can be completely blocked or suffer long delays, future investors may be deterred from similar schemes, and there is a risk of further eroding the public trust that is essential in making huge technological and social shifts.

“The cases focus not on stopping the transition, but on shaping the way it takes place, from the perspective of rightsholders themselves"

BHRRC is at pains to point out that many people who file them understand the risks of climate change, which is itself the greatest threat to human rights. But climate is not the most pressing challenge for every community and neither its harms nor the benefits associated with some solutions to it are distributed equally.

“The cases focus not on stopping the transition, but on shaping the way it takes place, from the perspective of rightsholders themselves,” says the report.

In a working paper on just transition litigation published earlier this year, legal experts Savaresi and Margaretha Wewerinke-Singh say these lawsuits are usually “a last and often only resort” for claimants. “While human rights may protect interests that might seem to be at loggerheads with climate action, these tensions should not be regarded as dysfunctional. Instead, they emphasise the need to develop a rights-based approach to the energy transition and to net zero emissions, shining a spotlight on those most affected by the climate emergency and by climate change responses.”

Fast because it’s fair

Having made a stab at defining just transition litigation, Savaresi now hopes more cases will become apparent and researchers will examine which ones are successful and why.

She believes studying these cases as a “discrete phenomenon” can help governments craft better laws and policies. A case in point is Mexico - a key Latin America wind power hub - where legal resistance to wind projects has spread nationwide, causing a serious problem for its incoming president.

It also mitigates the risk of exacerbating existing inequalities. “If you do the just transition right, then workers, communities, the private sector and states really can benefit from it,” says Elodie Aba, senior legal researcher at BHRRC.

Furthermore, it makes poor business sense for a company to leave itself open to these kinds of lawsuits. As well the legal fees and hefty potential fines and damages, protracted litigation raises project costs and damages corporate reputations.

Aba says the growing prevalence of just transition cases should be a “red flag” for companies and investors associated with renewable energy. She notes that the private sector has been dealing with the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights for well over a decade, “so those risks that we have identified, companies know them well”.

Jamaican courts are still tussling over the case led by Victoria Grant, as well as another which also claims breaches of constitutional rights. But The Wave understands that a complaint about the industry has been sent to the new UN special rapporteur on the human right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment so whatever happens the problem is not going away any time soon.