Why 2023 will be a watershed year for climate litigation

Over the past twelve months, courts from Indonesia to Australia have made ground-breaking rulings that blocked polluting power plants and denounced the human rights violations of the climate crisis. But this year could be even more important, with hearings and judgments across the world poised to throw light on the worst perpetrators, give victims a voice and force recalcitrant governments and companies into action.

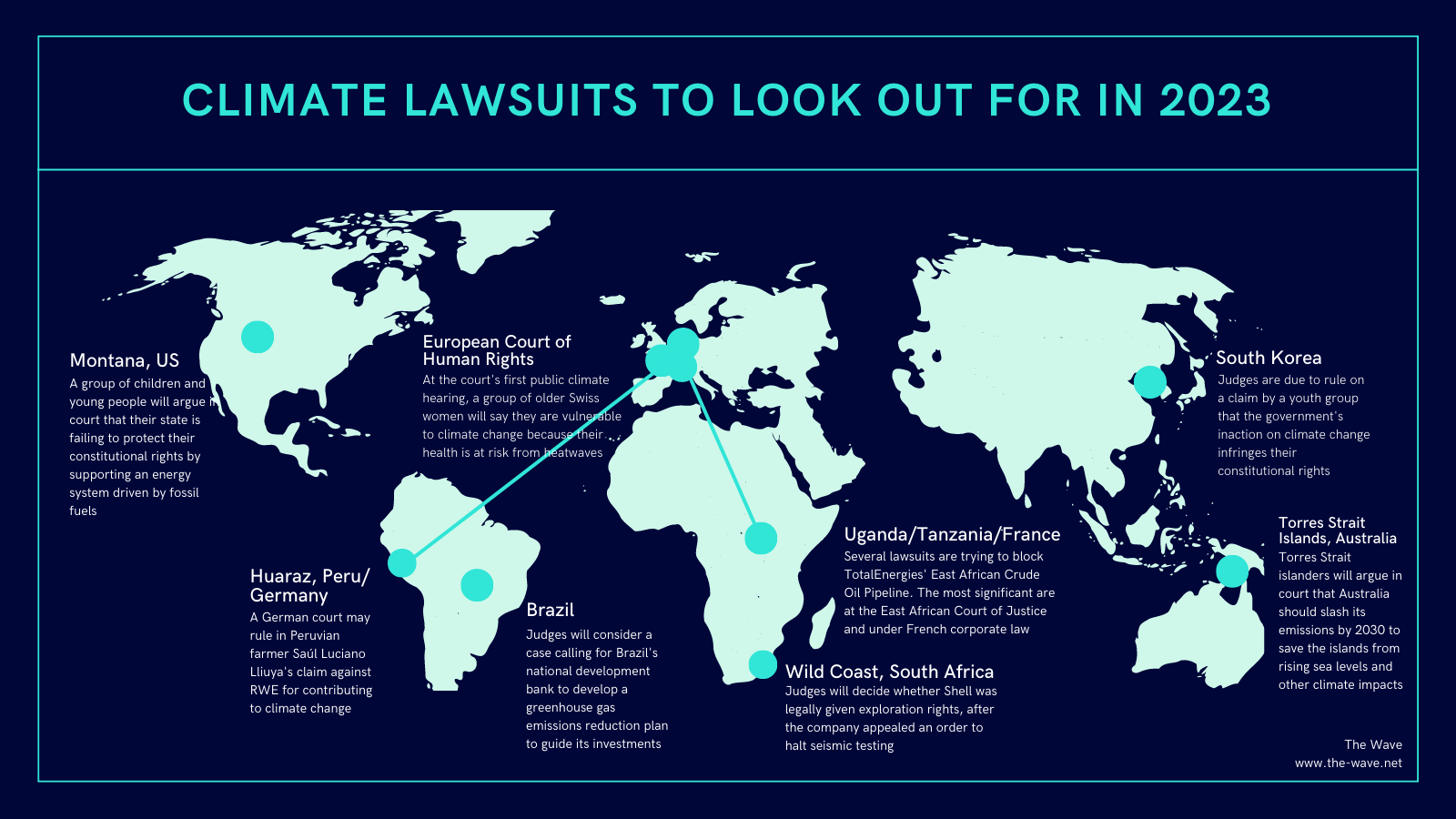

Although the bulk of climate lawsuits have been filed in the US, most of these have been thrown out of court or bogged down in procedural arguments. This year will, however, finally see a case go to trial when a group of children and young people between the ages of five and 21 square off against Montana.

Over two weeks in June, they will argue that the US state is failing to protect their constitutional rights, including the right to a healthy and clean environment, by supporting an energy system driven by fossil fuels. They will also say climate change is degrading vital resources such as rivers, lakes, fish and wildlife which are held in trust for the public.

“Never before has a climate change trial of this magnitude happened,” says Andrea Rodgers, senior litigation attorney with Our Children’s Trust, which is behind the case. “The court will be deciding the constitutionality of an energy policy that promotes fossil fuels, as well as a state law that allows agencies to ignore the impacts of climate change in their decision making.”

She said the watershed trial would be watched around the world and “is set to influence the trajectory of climate change litigation going forward”.

Other cases against US states could also be given permission to go to trial.

To the north in Canada, a ruling is expected this year in the country’s first climate lawsuit to have had its day in court. Seven young people, fronted by now-15-year-old Sophia Mathur, made history last autumn when they challenged the Ontario government’s rollback of its 2030 greenhouse gas emissions reduction target.

And to the south in Mexico, Greenpeace and groups of young people have led several important court cases challenging the slow pace of the country’s clean energy transition. In one, the Supreme Court is due to decide whether they have standing to bring their case.

In the rest of Latin America, which has pioneered innovative approaches in climate litigation, legal action will increase and improve next year, says Javier Davalos González, senior lawyer at the Interamerican Association for Environmental Defense (AIDA).

South Africa - already a hotspot for climate litigation within the African continent - could see a whole new set of lawsuits filed this year, as well as decisions in several important cases. One, a constitutional challenge to the country’s plan to build new coal-fired power stations during the climate crisis, was heard in November and a ruling is expected soon.

There are also hopes that Uganda’s High Court might finally conclude a case filed more than a decade ago by a group of young people, who argue their government is failing to preserve a healthy atmosphere as a public resource for both present and future generations.

Meanwhile, the Australian crucible of successful climate litigation will hear a class action case in June led by Torres Strait islanders Pabai Pabai and Paul Kabai, who argue the state should cut its emissions by 74% by 2030 to save their islands from rising sea levels and other devastating climate impacts.

A hop away in New Zealand, the Court of Appeal is expected to hear Northland iwi leader Mike Smith’s appeal against the High Court striking down his claim against the New Zealand government, in which he sought a declaration that it had breached its climate obligations.

And a decision is expected soon in a case filed by a youth group claiming the government of South Korea’s inaction on climate change infringes their constitutional rights.

Chinese courts, a surprisingly welcome venue for environmental lawsuits, have shown a growing appetite for climate litigation and action could be taken this year against provincial governments or cities.

On the other side of the world, the European Court of Human Rights has several climate cases on its books, all of which argue that government inaction in limiting dangerous global warming risks basic human rights such as health and life.

At its first public climate hearing in March this year, a group of older Swiss women known as the KlimaSeniorinnen Schweiz will say they are particularly vulnerable to climate change because their health is at risk from heat waves. They will get to make their arguments in front of the court’s Grand Chamber, which is reserved for the most serious cases, and will do so supported by two prominent British lawyers - Jessica Simor and Marc Willers.

Although this is a European case, it will cause international ripples. Kelly Matheson, deputy director of global climate litigation of Our Children’s Trust, which is advising on climate science in three cases before the court, said the decision by the court’s 17 judges would have a “profound effect on courts throughout the world as their finding will inform and influence the decision made in other judicial processes”.

At national level, campaigners will be asking judges to make climate orders against the governments of Italy, Belgium and France, following a string of successful similar European cases.

Sarah Mead, co-director of the Climate Litigation Network, says these cases are crucial because a positive outcome can enhance government accountability, particularly in OECD countries with significant historical responsibilities and more capacity to cut their emissions. They also help “narrow the global emissions gap and further foster citizens' mobilisation on the need for stronger climate action”.

She adds that the Climate Trials campaign, launched last year to threaten governments with legal action if they did not act, will ramp up.

There will be movement on an international level too. Early this year, the UN will vote on a key resolution about human rights and climate change. If passed, the International Court of Justice will have to provide an advisory opinion on the obligations of states under international law to protect the rights of present and future generations against the adverse effects of climate change. This work has been led by vulnerable island state Vanuatu, and now has support from governments all around the world.

Private sector

It’s not just governments in the firing line; climate litigation against the private sector will continue to grow.

In the US, there might finally be an answer to the question of which courts will handle the plethora of lawsuits against the fossil fuel industry. Companies have been pushing to have these cases heard at the federal level, where they believe they stand more chance of success, but judges have consistently ruled against them.

The Supreme Court has been asked to intervene, and if it takes up the case next year it may finally draw a line under the issue.

Richard Wiles, president of the Center for Climate Integrity, says that if the Supreme Court agrees with federal judges it would remove one of the last procedural hurdles and mean cases can start to move on to talk about the actual issues at stake - were the actions of fossil fuel companies reasonable and what responsibility do they bear?

Following pre-Christmas wins against billionaire Clive Palmer’s attempt to build a huge thermal coal mine and Santos $4.7 billion Barossa offshore gas project, Australian climate campaigners are now on tenterhooks awaiting a decision on their challenge to Woodside’s $16bn Scarborough gas project because of the impact of its greenhouse gas emissions on the Great Barrier Reef.

And, in another case fronted by Northland iwi leader Smith, New Zealand’s Supreme Court will decide whether a challenge against seven of the country’s largest polluters and fossil fuel producers, claiming injury from their ongoing emissions, can go to trial.

Over in Germany, there is likely to be a ruling in a landmark lawsuit brought by Peruvian farmer Saúl Luciano Lliuya against RWE for contributing to climate change. The court sent judges to Peru last year to determine the level of damage, and its decision will be very closely watched by corporations of all stripes.

Germany is also home to a group of cases filed against car manufacturers. One claim against Mercedes-Benz was rejected last year, but others could proceed further.

Following a landmark ruling last year that recognised the Paris Agreement as a human rights treaty, Brazil’s courts are expected to rule on a case brought against Brazil's national development bank (BNDES) and its investment arm BNDESPar by Brazilian NGO Conectas Direitos Humanos which wants them to develop a greenhouse gas emissions reduction plan to guide their investments. It’s the first case of its kind against a development bank anywhere in the world, and could have significant repercussions on wider climate finance.

Several lawsuits have been filed to try to block TotalEnergies’ controversial East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP). One brought by civil society organisations from Uganda and Tanzania at the East African Court of Justice has been bogged down by jurisdictional arguments. But another filed under a novel ‘duty of vigilance’ law in France had a hearing in December and there could potentially be a ruling this year.

And in South Africa, the courts will decide whether Shell was legally given exploration rights off the ecologically sensitive Wild Coast, after Shell appealed an order to halt seismic testing.

Next year might also see movement in Shell’s appeal against a landmark ruling by a Dutch court, which in 2021 ordered it to cut its carbon emissions by 45% by 2030. Although the court was clear that Shell must begin complying with the ruling straight away, Milieudefensie (the Dutch arm of Friends of the Earth), which brought the case, does not think it is doing enough to meet the target. In the meantime, Shell has moved its headquarters from the Netherlands to the UK.

Shell’s directors too will be under an unprecedented level of scrutiny this year. ClientEarth sent a letter to the company’s board in 2022, warning that it was prepared to start a legal challenge in the UK if Shell does not handle its climate risks better. If ClientEarth follows through, this would be the first derivative action anywhere against a board for failing to consider efforts towards achieving net zero.

When it comes to greenwashing - a fast-growing area of climate litigation - expect to hear more on allegations that Dutch airline KLM’s adverts promoting the company's sustainability initiative are misleading and claims that gas company Santos breached Australian corporate and consumer law over clean energy and net zero plans.

Whatever happens in those cases, expect to see many more lawsuits filed this year, as well as more creative uses of the law. These will be filed against governments of all levels, based on the most cutting-edge science, as well as against companies.

The financial sector, in particular, is likely to be a big target, and there will be continuing waves of related litigation targeting plastics and biodiversity loss. This year is “shaping up to be a really important year for climate litigation,” says Mead.